Ganesh Tripathi

Graduate Student Spotlight

by Jessica Fisher

photos by Shaun Ring

Most people in Kentucky associate the relationship between the state’s water and its limestone geology with world-famous bourbon and strong competitive thoroughbreds.

For Ganesh Tripathi, a graduate student in the Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences at the University of Kentucky, it was his interest in groundwater systems, and how limestone affects such systems, that brought him to Lexington, Ky., from Nepal in 2007.

So, besides unique groundwater systems, top-rated horses and the best bourbon in the world, just what is so great about limestone? As Tripathi’s research indicates, it is not always as picturesque as the Kentucky landscape may suggest.

Tripathi first became fascinated with karst groundwater systems after receiving a master’s degree in geology from Trubhuvan University in Kathmandu, Nepal, in 2001. He went on to work for Nepal’s government in the Department of Mines and Geology where he grew increasingly interested in water contamination within different systems.

This interest was piqued when he discovered professor Alan Fryar from the University of Kentucky. Though the topography in Nepal may be different from Kentucky, one common denominator is limestone; both Nepal and Kentucky have plenty. After connecting with Fryar and realizing the shared parallels in their research he made the trek to UK.

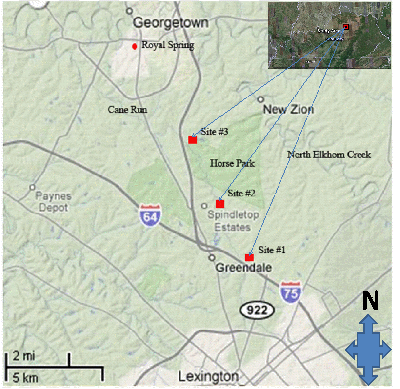

Tripathi, along with Fryar, Jim Dinger, Jim Currens and Randy Paylor of the Kentucky Geological Survey (KGS), used geophysical methods to explore conduits in the Royal Spring groundwater basin. Royal Spring is the main source of drinking water for Georgetown. The headwaters of the Royal Spring groundwater basin are in northern Lexington, including the area traversed by I-75/I-64 and the area underlying Spindletop Farm.

In this area “the ground water when running against limestone flows in a channel. The water makes a concentrated flow below the surface and it makes the flow faster than in other kinds of groundwater systems,” said Tripathi.

He added, “If there is a source of pollution connected to these conduits, then just as the water moves at faster rates then so will the pollution.”

Tripathi’s research, funded in part by the UK College of Agriculture and the KGS, noted, the Royal Spring groundwater basin is an environmentally sensitive area with potential major impacts on water quality. By pinpointing the location of the karst conduits (an area of limestone terrain characterized by sinks, ravines, and underground streams) Tripathi and other geologists can aid in monitoring and determining possible sources of groundwater contamination.

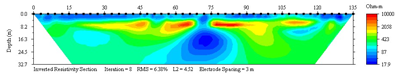

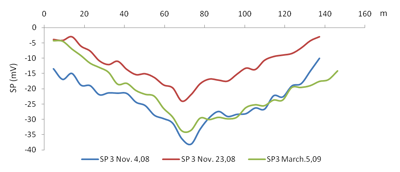

In order to determine the location of such conduits, Tripathi used electrical resistivity (ER) and self potential (SP) methods. Then the KGS drilled a well that intersected a water filled conduit at the precise location indicated by the geophysical methods. Not only are these geophysical methods that Tripathi applied less costly than drilling, they also hold great promise for delineating karst conduits.

Tripathi recently finished defending his master’s thesis which he said was “stressful but interesting,” and plans to enjoy a semester break, back home in Nepal, before returning to pursue a Ph.D. in the department of Earth and Environmental Sciences in January. As one might expect from the University of Kentucky’s prestigious pool of professors, Fryar has become a great confidant to Tripathi and was a defining factor in his decision to move forward at UK. “He is a very supportive mentor and ready to help at any time.”